When Was The Kodak Camera Invented

The Kodak Camera

From ETHW

Jump to:navigation, search

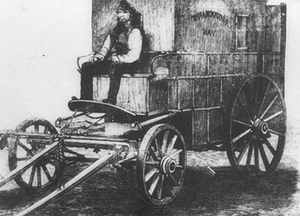

These images illustrate the equipment that the professional person lensman would take to transport effectually to accept moisture-plate photos in the mid-19th century.

The Digital camera invented by Steven Sasson in 1975

125 years ago, George Eastman introduced the "Kodak" camera. He had identified a withal-untapped human being want to record the images of everyday life. In so doing, Eastman transformed photography from the esoteric pursuit of the few into a truly mass cultural phenomenon. This small camera "democratized" people'southward admission to film taking. The Kodak brand proper name quickly grew into a world-wide icon. By the 1960s, the term "Kodak moment" had become part of the American popular lexicon. People'due south want to capture every aspect of their lives, which Eastman had first unleashed 125 years ago, then found new technological enablers in the belatedly 20th century with the appearance of Charged-Coupled Devices (CCD). The stage for the elimination of film was set. Hither, as well, Kodak did pioneering piece of work. And yet, even though a division of Kodak had been ane of the first to experiment with CCD-based photography, Kodak was not nimble enough to adapt to this revolution in photography. At the center of the problem was a corporate culture that was securely rooted in the 19th century innovation of motion-picture show, which ironically had been the footing of Kodak'due south emergence as a concern empire.

To understand the profound significance of film, one must appreciate the complexity of the photographic practices that emerged in the decades immediately following the birth of photography. For the thousands of years only the artist could capture visual reality. Even so, painting, as a mode of recording moments in life was only available to a tiny fraction of society. Only a minute portion of lodge could committee an artist to create a portrait, a family scene, or a favorite landscape. The vast majority of people had absolutely no visual remembrances of their lives. Then at the outset of the 19th century, as Humphrey Davy wrote in 1802 in the Journals of the Royal Institution of Swell Britain, Thomas Wedgewood, the son of the famous industrialist Josiah Wedgewood, had plant that paper moistened with a silverish nitrate solution would undergo color changes, from shades of grey and brown and finally to black, when exposed to calorie-free. Wedgewood, as Davy went on to report, had failed in all his experiments to betrayal an epitome on the paper using a "photographic camera obscura." Merely now the race was on to notice a fashion. In 1839, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1789 - 1851) provided the first practical solution. He used a copper plate coated with iodized silver. The image, nonetheless, just became visible when mercury vapor was passed over the copper plate. For the reader, this method may seem far from practical, and even unsafe, merely at the time, it offered the kickoff reliable way to produce good quality images. Since Daguerre's procedure produced a positive, making expert reproductions of the photograph was very difficult. So the idea of the negative was born.

For the next half century, the key technical progress in photography revolved effectually the glass plate negatives. For several decades, the "wet-plate" offered the best negative. Information technology produced excellent images, but its use was very intricate, exceedingly cumbersome, and quite expensive. But earlier shooting, the photographer had to evenly distribute an iodide or bromide collodion over a large thick glass plate. Then in a nighttime room, immerse the plate in silver nitrate. From the bath, the photographer had to quickly become the plate into the camera without exposing it to light. The lensman had simply minutes to get the plate adult after it had been sensitized. When not in a studio, photographers had to carry all the plate processing and developing paraphernalia where ever they went. Just a professional person, or a highly motivated hobbyist, had the skill, and upkeep to use wet plates. George Eastman was such a hobbyist.

By 1877, the 23-twelvemonth-old Eastman was on his manner to a successful cyberbanking career in Rochester. Then he came under the spell of photography. Eastman invested in all the expensive equipment needed to take and develop moisture-plate photographs. He even paid a local professional person photographer to teach him all the basics. Eastman's thoughts chop-chop turned to the obstacles that the crushing wet-plates posed to growth of photography. In 1878, he read an account in the British Journal of Photography, of a new formula for an emulsion that eliminated the need to soak the plates. It was a "dry-plate." He immediately threw himself into the idea of producing his ain dry-plates as a way to make photography easier for himself. With admittedly no training in chemistry, Eastman proceeded by trial and mistake, avidly read all the photographic journals from away, and questioned anyone with more noesis than him. While all the same working equally a banker, Eastman tirelessly pursued his passion every day afterwards piece of work and into the wee hours. Within a couple of years, not simply had Eastman developed a formula of ripened gelatin and silvery bromide, but he also filed a patent for motorcar that could apply his formula on drinking glass plates "in large numbers…with great rapidity and of improve quality than is better than is practicable past handwork." His patent filing reveals his early vision for the photographic manufacture -- one based on standardization and mass-production, rather than one rooted in custom hand-made production every bit it still was at the end of the 1870s. In 1880, Eastman established the "Eastman Dry Plate Company" to manufacture and sell dry out-plates. Eastman'south new business started to grow as word got out near the loftier quality of his dry-plates.

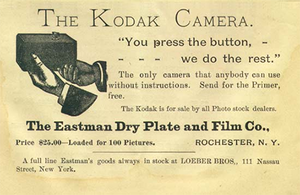

Initially, Eastman's dry-plates targeted the professional and the sophisticated amateur. Highly motivated and skilled, these two groups, in Eastman's heed, "valued photography every bit something between a challenging arts and crafts and fine art form." But Eastman'due south instincts told him that, with the right technology, a very different and much larger form of customers could emerge. He sensed the corking possibilities of a mass market populated by people who had admittedly no interest in the technical or creative challenges of photography. Instead their only desire would be to visually record every aspect of their personal lives. Stride by footstep, through the 1880s, Eastman'due south business was building up all the technical components needed to transform photography into an activity requiring little or technical no skill. Finally, in 1888, with all the technical components in place, the Eastman Dry Plate & Film Co., as his visitor was now called, launched the product that revolutionized photography.

The "Kodak" camera was a simple, small box camera that came with a pre-loaded curlicue of movie of a 100 shots. At $25, it was not cheap. Only it provided the convenience for which the middle form was willing to pay. The advertisements for the Kodak camera proudly proclaimed: "Anybody tin utilise it." With the Kodak, Eastman proclaimed, "photography had been reduced to a cycle of 3 operations: pull the cord, turn the key, and press the push." But information technology was Eastman'southward idea of offering a service to process the pic negatives and produce the prints that gave the camera greater mass entreatment. Gone were the chemicals, the developing and printing equipment, and the dark rooms. Instead, for $10, the user of the Kodak could simply ship the camera direct back to the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Co. in Rochester, where the camera's 100 negatives would be developed. The company would then mail dorsum the prints along with the camera fully loaded with film and set to go. The brilliance of this business strategy was captured in the marketing slogan, "you press the push button, nosotros practice the rest." The Kodak camera became all the rage and rapidly spread through middle grade America. In 1892, the company was renamed the Eastman Kodak Co. During the next hundred years, the company grew into a global industrial behemothic with an impressive list of innovations in film and imaging. The Kodak make had become a global icon.

Digital engineering brought an end to film photography for the consumer market, and the collapse of the Kodak corporate empire. And yet, ironically, Kodak was a pioneer in CCD photographic camera engineering science. It all started in 1974 with a 20-second conversation between Steven Sasson, an electric engineer working in the R&D lab of Kodak's Apparatus Sectionalization, and his boss Gareth Lloyd. Fairchild had just introduced one of the first CCDs to the market. The search for a solid-country replacement for the vidicon, the video camera tube, animated much of the interest in the CCD in the early 1970s. But it was seen as long-term undertaking. The Fairchild CCD was far from beingness of use for commercial video cameras. So the immediate commercial utility of Fairchild's CCD was nevertheless unclear. Lloyd asked Sasson to explore the utility of the CCD to Kodak'south operations. Could it be used in any way, perhaps every bit a measuring tool in manufacturing? In Sasson'south words, this was a "filler project"-- an open up-concluded project with no goals. Sasson decided that building a camera to take photos was the best way to explore the characteristics of the CCD. Other than the $100 to purchase the Fairchild CCD, he had no upkeep. He could only employ spare parts laying effectually at Kodak. A year after, in 1975, he and two part-time technicians succeeded in edifice a device that took black & white digital pictures, stored them on digital cassette tape, and played them back on a television. Weighing in at viii lbs. the photographic camera was rather large. The CCD could only produce images 0.01 megapixel in size. But it was the get-go digital camera. For this achievement, President Obama presented Sasson with the National Medal of Engineering science, in 2010.

Kodak middle direction did not know what to make of Sasson's digital camera. They thought it was "likewise far out for serious considerations." Compared to film, its images were crude and no one, including Sasson, had any idea when this applied science could ever produce images to rival film quality. Direction was convinced that no one would want to view images on a television. But more chiefly, management could not envision how the digital camera could exist made to fit into any portion of Kodak'due south operations. Center management never let Sasson demonstrate the digital camera to the company'due south top executives. In fact information technology was nearly three decades later on when company made the story public. In the 1980s and 90s, as CCD technology improved, Kodak management believed that the market for digital camera would be the professional photographer. The visitor devoted a lot of R&D to digital imaging technologies, all for the purpose of producing high-end products. With these R&D efforts, Kodak clustered the single largest pool of intellectual property tied to imaging technologies. And yet, in all these efforts, very lilliputian thought was given to the mass consumer market place. For Kodak, its long-standing and highly profitable film-based business still responded to the average consumer's needs. By the time, Kodak realized the error of this cess, information technology was too late.

In 2013, just 125 years after George Eastman put the revolutionary Kodak camera on the market that launched the Kodak business empire, the visitor was forced to sale off one,100 of its patents equally part of bankruptcy proceedings. These patents dealt with image capture, manipulation and sharing technologies. A consortium, which included companies like Google, Microsoft, and Apple, was interested in buying up these patents. The sale produced far less than the $2 billion that Kodak had hoped for. Part of the problem was that the many of these patents were of dubious value to the consortium, because Kodak was already licensing them to competitors like Samsung and HTC.

George Eastman'due south genius lay in seeing the enormous business potential in democratizing photography; making moving picture taking very simple and affordable. "Y'all press the button, we practice the rest" was the foundation of the visitor's business model. In the 21st century, with the Cyberspace, social media, inexpensive and small digital cameras, and the introduction of CCDs into cell phones, the process of democratization expanded dramatically. "Nosotros do the remainder" no longer had any relevance. All effectually the globe, even in the poorest areas, people were snapping countless pictures and displaying them instantly. But of more profound significance, people wanted to share them in existent-time across the globe. It'due south no longer almost memorializing "Kodak moments." It's at present nearly sharing the "Kodak moments" with the world.

Further Reading [edit | edit source]

Carl Westward. Ackerman, George Eastman (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1930). This biography was authorized by George Eastman.

Elizabeth Brayer, George Eastman: A Biography, (Rochester, NY: Rochester University Printing, 2006). This a reprint of the volume first published in 1996 past John Hopkins University Press.

Douglas Collins, The Story of Kodak, (New York: Harry North. Abrams, Inc Publishers, 1990)

Henry C. Lucas Jr. and Jie Mein Goh, "Disruptive technology: How Kodak missed the digital photography revolution", Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 18 (2009), 46-55.

Steven Sasson's public lecture at the Linda Hall Library

Source: https://ethw.org/The_Kodak_Camera

Posted by: crewsmistne.blogspot.com

0 Response to "When Was The Kodak Camera Invented"

Post a Comment